Shota Bostanashvili and Architecture’s Hidden Language

Positive Stories

1 427

0

“Architecture is silence that needs to be heard.” – Shota Bostanashvili

Georgian culture often struggles with a painful paradox — forgetting its greatest names and moments. This forgetting can happen for many reasons: inertia, deliberate neglect, or simply because life gets too busy. It becomes especially clear during times of unrest, when society’s focus shifts away from art and culture.

But it’s up to us — the generation raised in peace — to remember and honor those forgotten voices. Shota Bostanashvili is one such figure whose work and ideas still shape our world today. He was an architect, thinker, poet, and teacher whose legacy deserves to be celebrated.

Born in Tbilisi in 1948, Shota saw early on that architecture was more than a job — it was a universal language with the power to rescue space from dullness. After graduating from the Georgian Polytechnic Institute, he found himself caught between the rigid socialist functionalism and a rising wave of cultural idealism. But Shota chose neither — instead, he forged his own unique path.

"Poetics of Architecture" – An Expression of Architecture from Within

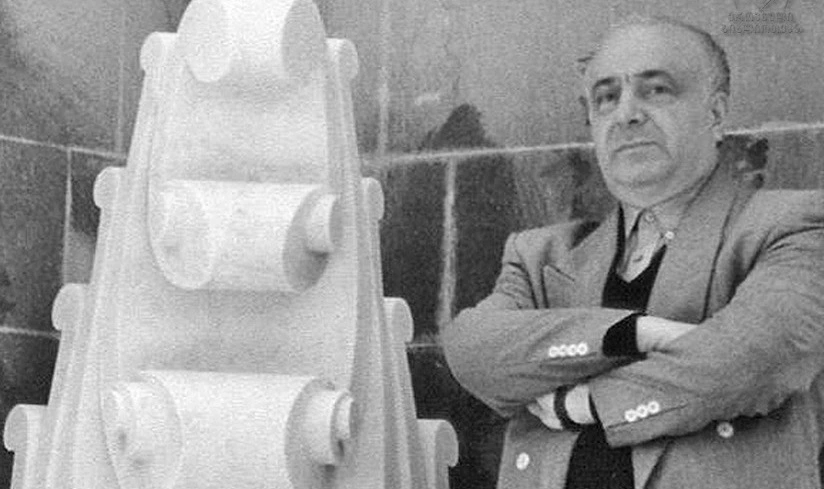

Beyond his hands-on work and research, Shota Bostanashvili shone brightest in the realm of theory. In 1990, he articulated a compelling vision he called the poetics of architecture. This was far more than just an abstract idea — it was a manifesto, a way of seeing buildings not merely as physical structures but as living poems.

His theoretical outlook was deeply influenced by great minds such as Bakhtin, Deleuze, Guattari, and Mikhail Epstein. Drawing from their philosophies, Bostanashvili crafted the concept of the poetics of space. He viewed architecture as a language — a discourse of space itself. It is a tangible, physical reality, yet it simultaneously carries rich cultural, psychological, and semiotic layers of meaning.

Through this lens, every building becomes more than stone and steel; it is a narrative, a symbol, a poem in which space speaks and stories unfold.

For Bostanashvili, architecture is a poetic discourse full of signs — where every building and city reads like a text, open to endless interpretation and reinterpretation.

Though often labeled a postmodernist in today’s architectural world, his vision actually goes beyond—and sometimes even contradicts—the core ideas of postmodernism. Rather than simply embracing it, he used its foundations to build a broader, deeper theoretical framework.

He saw architecture as a metaphorical language: walls symbolizing longing, stairs representing the movement of thought, and ceilings evoking suspended time. To him, architecture was not just functional; it was philosophical, psychological, and poetic.

Bostanashvili was also a poet. His 2008 poetry book, Fiery Speech, is available online and shows the deep connection between his literary and architectural creativity. This intersection between poetry and architecture defines much of his work, sometimes even expressed through performance art.

One of his architectural masterpieces was the “Palace of Poetry,” located on Amagleba Street in Sololaki. This unique building, inspired by Galaktion’s Artistic Flowers and shaped like three white bouquets, won three major international awards, including the Silver Medal at the International Triennial of Architecture and the Prize for High Architectural Mastery.

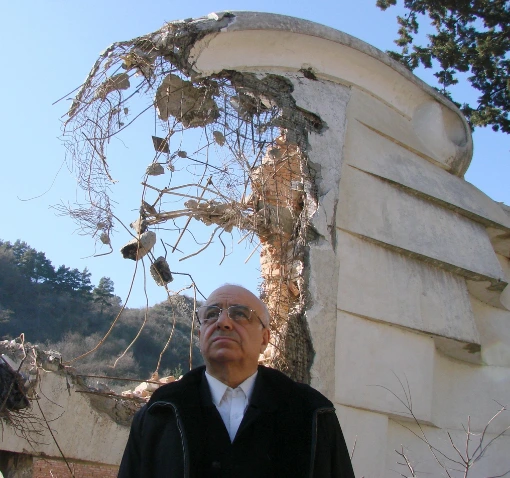

Sadly, the “Palace of Poetry” fell victim to Georgia’s modern political and economic turmoil. The memorial building was left abandoned for years before bureaucracy sealed its fate and it was completely destroyed.

As the building was being torn down, Shota Bostanashvili stood nearby for three days, quietly reciting poetry over the sounds of demolition. These powerful images capture the very essence of modern Georgia — a nation caught between preserving its past and facing relentless change.

Some architects simply design buildings, while others write with space—crafting a language that people must read, experience, and feel. The “Poetry Palace” stands as a prime example of this, along with Shota Bostanashvili’s other works.

Many of Shota Bostanashvili’s projects remained unrealized due to their theoretical depth and complexity. These include designs for Khevsurian villages like Khakhmati and Biso, a swimming pool, the international tourist complex "Mziuri Valley" in Bakuriani, a cultural center in Abkhazia’s Gulripshi, a children’s city, the Maltakvi forest-park, and others. Yet, some of his works were completed — like the bread factory in Tbilisi, which masterfully blends industrial architecture with aesthetics, turning everyday routine into art.

Bostanashvili also contributed to sculpture. Among his notable works is the “Glory to Labor” monument in Kutaisi (1976), and especially the “Cube of Memory” in Senaki (1975), created with sculptor Vazha Melikishvili. This monument was unique across the Soviet Union — instead of glorifying war heroically, it revealed its cruelty, horror, and helplessness. Its anti-Soviet message stood out not just in content but in form: a crushed cube at the center, surrounded by sculptures depicting the brutal realities of war.

Alongside his practical and theoretical work, teaching played a vital role in Bostanashvili’s life. His students recall lectures that lasted five to six hours, filled with passion and deep engagement. He didn’t just teach architecture; he taught how to think. Shota Bostanashvili passed away during a lecture in 2013.

His ideas live on — not just in buildings, but in the memory of space and the minds of architects. He didn’t build towers; he built a horizon of thought upon which future generations will stand.

RELATED NEWS

Positive Stories / Animals

An innovative camera for filming birds that also "treats"..

Animals

Deer rescued after tire removed from around its neck..

Positive Stories

Where, when and how to plant a tree?..

Positive Stories

The Secret Life of Forests: How Nature Protects Itself and Why We..